- Home

- Isaiah Campbell

The Struggles of Johnny Cannon Page 3

The Struggles of Johnny Cannon Read online

Page 3

Sora smiled and nodded.

“When are you due?” Mr. Thomassen said.

Martha plopped down next to Sora and put her arm around her.

“In October,” she said, “and she doesn’t have a place to stay.”

“Not true,” Pa said. “She can stay here.”

“Pa!” I said. “What about the hotel or something?”

“What?” he said. “No, nonsense. This place could use a woman’s touch. Sora can stay in Tommy’s room. It’s only right.”

She hugged his neck and I reckon the baby took a jab at him too. He didn’t seem to mind it. He put his hand on her belly to feel it contort and he laughed when it did.

I announced that I was going to get her luggage and Carlos offered to help me, but then Short-Guy said he’d do it ’cause he needed to talk to me about something. Which made my stomach get back into the bag of knots it had been when I first saw him. I hurried outside and he hurried to follow me.

I started grabbing bags real quick and he stopped me.

“How much do you know about what your father is doing with Mr. Thomassen?” he asked.

“Why?” I asked, and I felt all them knots tighten up in my stomach. “Is he getting into trouble again?”

“No,” he said. “Not—just tell me, how much do you know?”

“Only that they call themselves the Three Caballeros, like that old Disney cartoon. And that Carlos goes away for two or three days to do jobs that Pa finds for him. And that not a one of them talks about it none.”

He listened real intent to that.

“And that’s all?”

“Yup.” I pulled out another of Sora’s bags from the truck. “Why? What’s up?”

“Have you mentioned their name to anyone? The Three Caballeros, have you told anyone about that?”

“No,” I said. “Well, Willie, but he’s my blood brother, so I tell him everything.”

He nodded.

“Now, listen to me. I need you to answer this question completely, and don’t even think of lying to me.” He grabbed me by the shoulders, which was a little weird since he was an inch smaller than me. “Who have you told about Captain Morris? That he is your real father?”

“Only the folks that was in the room when I recorded my testimony,” I said. “So, the Parkinses, the Mackers—well, Martha and her ma, at least—and Mr. Thomassen and Carlos. Oh, and Pa, of course.”

He sighed.

“That’s more than I’d like, but it’ll have to do. It can’t go further than that circle. Do you understand me?”

“Sure, I guess,” I said. “Why, what’s going on?”

“Nothing you need to worry about. As long as you do as I say, nothing at all.”

Oh good. ’Cause there wasn’t nothing about what he said that made me worried or nothing. I was as cool as a cucumber now. A cucumber that was worried he might get shot in the head while he slept. That’d be a real pickle.

See, I wasn’t nervous. I was almost peeing my pants, but still, I had jokes to spare.

We headed back inside and went to carry Sora’s things up to Tommy’s room. She stopped me and told me to leave the duffel bag down there. When we came back down, she had a gift-wrapped box and a manila envelope sitting on the coffee table.

“What’s this?” I asked.

Sora smiled.

“Tommy made me promise I would come here to give you your birthday present. He wanted to make sure it was hand delivered.”

The whole room got quiet, the kind of quiet that makes the air start itching at you. Adding the itchy air to the nervous stomach I had from Short-Guy’s conversation, and I almost puked.

“What?” she asked. I looked over at Short-Guy, and he threatened my life with his eyes, so I had to come up with something else that was wrong.

“My birthday is in July,” I said. “You’re late.”

“Johnny!” Pa yelled.

“Really?” she said, real confused. “Then why did he say it was—” She shook her head. “Oh well. Tommy wasn’t exactly in the clearest state of mind when he and I were together in Mobile. He was so nervous about shipping off.”

“To Nicaragua,” Pa said.

That was a sputter in the conversation, and Sora seemed to get a little nervous over it. Or morning sick, there ain’t no real way to be sure with pregnant women. She shot Pa a glance, one of them “do you know what you’re talking about?” glances (or maybe one of them “I’m about to puke on your face” glances. Like I said, pregnant women).

“Did he tell you he was going to Nicar—”

“No, no, not Nicaragua,” Pa said, real nervous like, I reckoned ’cause he was worried she didn’t know what we knew. “My brain plays tricks.”

“Where did he tell you he was going?” she asked.

Pa shot me a look.

“Korea,” I said.

“Right, Korea,” Pa said.

“Korea,” she said, and she looked a little more sure of herself. “He told you Korea?”

“Sure did,” I said. “ ’Cause that’s where he went. Not to Nicaragua, or Narnia, or any of them other places.”

“Exactly. Korea,” she said.

“Yup, Korea,” I said.

She peered into my eyes, then over at Pa’s, and then she let out a satisfied sigh.

“Anyway.” She handed me the manila envelope. “Here, I don’t know what’s inside of this and I’ve been dying to see.”

Short-Guy cleared his throat and I knew why. He was naturally suspicious anyway, and that whole talk between me and her and Pa was enough to get him calling for backup. ’Cause Tommy hadn’t gone to Korea. That was just his cover story. He went to Nicaragua to train the Cuban exiles for the Bay of Pigs invasion. So it probably didn’t sound right to Short-Guy that Tommy’d have told the woman he was going to marry a lie like that. But that was ’cause Short-Guy didn’t know Tommy. Tommy was inclined to lie to women.

I opened the envelope and slid out three comic books. All of them Superman comics, of course. ’Cause nobody knew me better than Tommy.

“Read the letter,” she said. “Out loud, please.” She seemed real excited about it. Everybody else, too. So I cleared my throat and did a quick scan so I wouldn’t stumble over no words.

T. Cannon

Springfield, Fla.

April 7, 1861 1961

Dear Johnny,

Wow, my FIRST LETTER! Can’t believe I haven’t ever written a first letter to you before. But I figured, if there was ever a time to write a first letter, it would be on your birthday. Wish I could remember when it is. It’s in the summer, but I don’t think it’s a J month, so August? Yup, that’s when you’ll get this first letter.

But what I really need to say is

Knowing every elected politician yesterday only undoes right belief. Looking over our deeds satisfies as failure elevates failure, rusting our men. Hear Antonia + Rose’s message.

Anyway, I love you, little brother. I also love the lady that brought you this first letter. Treat her right.

Tommy Cannon

I tried to read it out loud, but I couldn’t even get past the date. It was so dadgum weird, it made my brain hurt to think about speaking it. I folded it up and mumbled a thank-you to her.

“Too emotional,” Carlos said. “I understand, compadre.”

Everybody else seemed to think that was a good explanation, so I let it be.

Sora slid the gift across the table.

“Open it,” she said. “I think you’ll like it. Tommy was always saying how much you like superheroes.”

I unwrapped the present and opened the box, and for the first time I felt a tinge of that same disbelief that Short-Guy had been showing on his face. ’Cause either Tommy had been running on a few bottles of Jim Beam, or that present hadn’t come to me from Tommy. Not a chance.

It was a statue of Robin, the Boy Wonder’s head. And Tommy knew, more than anybody else, how much I hated Robin. When I was ten, I’d even gone thro

ugh all his Batman comics and cut out all the Robins just so I could burn them on our grill. Robin was a dadgum nincompoop who ran around in women’s underpants. Worst superhero ever.

I looked around the room, a tad bit worried that they was all going to start accusing her at once. It might not be good for the baby to have so many fingers pointed, and especially if they threw her out on her backside, well, it might give the kid a flat head or something. I got ready to start making excuses, just like I usually did for one of Tommy’s girls.

Pa stood up and picked up the Robin statue. Good Lord, was he about to smash it over her head? I jumped up to stop him.

“This—” he started, and I poised myself to jump in between them. “This is wonderful. Let’s put it over here on the mantel so we can all think of Tommy every day.”

Wait, what?

I looked at Mr. Thomassen. He didn’t never let nothing get past him. He’d probably cut right to the heart with whatever he said. I needed to figure out a good joke or something.

He was patting his eyes with his hanky. Okay, no joke needed. Which was good, ’cause the only one I thought of on such a short notice was the one about the car crank and the fella’s butt.

“Makes me think of my own brother,” Mr. Thomassen said. “I haven’t thought of him in a while.”

Whew. She was probably safe. I mean, sure, it was a little weird about the statue and all, but still. She was going to have a baby. That covers just about everything, doesn’t it?

I looked over at Short-Guy. Nope, apparently not. He was scowling like a judge at a hanging, and I don’t reckon he cared much about the baby or nothing else. There wasn’t going to be no making him happy about Sora.

And that made me as nervous as a cat in a room full of rocking chairs. Add that to what he’d done told me, and all of a sudden I needed to get some fresh air.

“I’ll be back in a bit,” I said. I grabbed the letter and headed out the door, and then I hurried to go find the only fella I could tell everything to.

I hurried over to Willie’s house.

Willie’s porch was a little cluttered when I got there. They had one of them porches that was designed to have family reunions on, and it looked like they’d had a church get-together just before I came over. His pa was the pastor of the church in Colony, which was the place in Cullman County where the black folk lived.

I knocked on the door and Mrs. Parkins answered it.

“Willie’s sick,” she said. “But you’re welcome to come in. We have lots of leftovers from lunch.”

“I heard he was sick,” I said. “That’s why I brung him something.” I looked around real quick and saw a tuna can that somebody’d put potato salad in. I picked it up. “It’s an old family remedy for a tummy ache.”

She gave me her usual suspicious look, which I’d grown to learn was what a mother does to a boy when she cares something about him, so I felt good. She took me down the hall to Willie’s room. As usual, I could hear him talking.

“Traversing the snowy mountains of the ice planet, Mercury is starving. He hasn’t eaten in days. His only rations he split between Smokey, his faithful canine companion, and the green, two-trunked elephant, the only creature that can safely navigate the treacherous terrain. Now, sitting in his camp, he watches both creatures sleep. Our hero must make the impossible decision. Which warm-blooded friend will be his dinner?”

Mrs. Parkins knocked on the door. Willie said an almost cussword that wasn’t and then we heard a ruckus that sounded like somebody with only one good leg diving across the room into his bed.

“Johnny’s here,” she said, and opened his door.

He was wrapped up in his blanket and blinking his eyes like he just woke up.

“I sure hope he don’t catch my chicken pox,” he said, then he coughed a few times. His ma shot him that same suspicious look.

“I thought you said you had the measles.”

“That too,” he said. “Dadgum, I might have to stay home from church for the next month, huh?”

She covered her mouth and I reckoned maybe she was protecting herself from his germs. Course, it almost looked like she was smiling, but there wasn’t no way that was true, so it had to be the germs thing. She left me and Willie alone, and as soon as she was out of earshot, he hopped out of bed.

“So,” he said, “did it work? Did you finally get your Happy Ending?”

I shook my head.

“Not even close. Pretty sure I’m further from kissing Martha now than I was yesterday.”

He sighed and went over to his bookshelf, where he had a whole row of red notebooks lined up. He pulled one off, which had a white label on the cover with the words “Operation Happy Ending” written in permanent marker. He opened to a page that had “Fishing Trip” written on top and he wrote, in big letters, FAILED straight across all the other writing. He turned to the next page.

“We won’t give up yet,” he said. “We got plenty more good ideas, and I got the equipment to make them all work.” He pointed at the top of the new page. “Next up is ‘Drowning.’ See, you’re going to fake like you drown and she’s going to give you mouth-to-mouth.”

“Does that count as kissing?”

“Maybe not when she first starts,” he said, “but when you’re done, it will.”

I shrugged. “Whatever, you’re the junior agent, not me.”

He nodded. “By the way, did you bring me back that walkie-talkie?”

“Dadgummit, no,” I said. “I left it at the cemetery.”

“The cemetery?” He flipped back to the fishing page in his notebook. “That wasn’t part of the plan.”

“A whole mess of stuff happened that wasn’t part of the plan,” I said, and then I told him all about visiting Ma and Sora showing up, and the baby that was Tommy’s. He was real interested in that and even fished a notebook off his shelf that said Tommy Cannon Case File and wrote some stuff in it.

“Why do you got a case file on Tommy?” I asked. “Dead folk don’t usually do much that needs investigating. Their ghosts might cause some mischief, but you ain’t supposed to look into that.”

“I have a case file on everyone,” he said. “It’s what Short-Guy said agents do.”

Now, he knew Short-Guy’s name, but since I couldn’t never remember, we both just called him Short-Guy behind his back.

“He was up there too,” I said. “Him and the Three Caballeros was having a meeting.”

“He’s up at your house?” he asked. “Dang it, and here I’m claiming to be sick. I wonder if I could fake a miracle or something so I could go see him.”

I went over and started fiddling with his notebooks.

“I wouldn’t. He scared the heck out of me. Practically said I’d be in danger of hellfire if I told anybody that I’m Captain Morris’s son.”

He pushed me away from his books.

“Really? Why?”

“He wouldn’t tell me. And then it got worse when he saw the weird letter and the stupid present.”

“A letter? What did it say?”

I got the letter out of my pocket and handed it to him. He read over it and his face showed that he thought it was funny business too.

“This is the weirdest dadgum letter I’ve ever read,” he said. “Who’s Antonia and Rose?”

I had to look at the letter again to see what he was talking about. Right there in the middle, it said to hear Antonia and Rose’s message.

“Don’t look at me,” I said. “I ain’t never heard of nobody around here by those names. I mean, if it really was 1861, like is scratched out, instead of good old 1961, I’d think he was maybe talking about Antonia Ford and Rose O’Neal Greenhow, the Confederate spies during the Civil War. They leaked information to the south about the Battle of Bull Run and a whole mess of other things. But it ain’t back then, so it could be anybody.”

He got a funny look on his face.

“When was he in Florida?” He pointed at that part at the top that said T. C

annon, Springfield, Fla.

“He wasn’t,” I said. “He probably wrote it at a bar in Springfield, Alabama, and was so shaky he didn’t finish out the first letter. I’m telling you, he was as drunk as a skunk on its twenty-first birthday.”

He nodded, but he kept right on staring at it.

“Mind if I hold on to the letter for a bit?” he asked.

“I don’t care,” I said. “I was going to put it in my keepsake drawer. Just make sure I get it back, okay?”

He put the letter up on his wall with a thumbtack.

“Sure,” he said. “Though, what if it ain’t really from Tommy? You want to keep it, then?”

“What you mean? Of course it’s from Tommy. That’s his handwriting. It’s his drunk handwriting, but still, it’s close enough.”

“Okay, but what if it ain’t?” he asked.

I hadn’t honestly thought of that. Maybe somebody was copying his way with a pen.

“If it ain’t from Tommy,” I said, “who’s it from?”

He shrugged.

“That’s what we’d have to find out.”

Dadgum, he’d been in secret agent mode for too long. Suspicious of a poor pregnant lady. That just wasn’t right.

But, now he had me thinking.

What if?

CHAPTER TWO

GROCERY LISTS

I was standing at the front of the classroom writing on the blackboard. I glanced down to make sure I was wearing pants. I was.

Dadgummit, that meant this wasn’t a dream.

It was the first day of school and Mr. Braswell, the brand-spanking-new teacher, was making good on a promise he’d made Mrs. Buttke, my teacher from sixth grade. When she found out he was going to be teaching us, fresh out of college, she went and made sure he was good enough to teach her precious kids. Which was us, I reckon. And apparently he’s real good at math and science and English. Heck, he sent us all a letter back in July making sure we all knew about prepositions and how they was the words you wasn’t supposed to end a sentence with.

But then she found out he’d just barely passed all his classes in history. And as far as Mrs. Buttke was concerned, history was the most important subject you could possibly learn in school. So she made him promise that he’d have a This Day in History for us every day, just like she had. And, since he wasn’t so good at it, he should have one of his students do it for him.

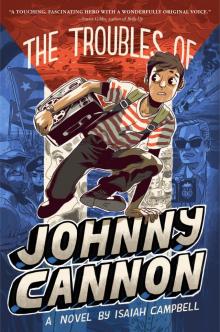

The Troubles of Johnny Cannon

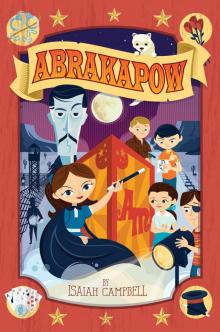

The Troubles of Johnny Cannon AbrakaPOW

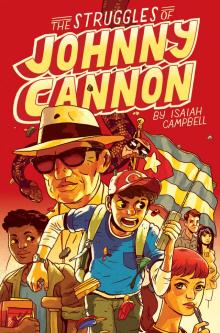

AbrakaPOW The Struggles of Johnny Cannon

The Struggles of Johnny Cannon